|

|

The Department of Egyptian Antiquities presents vestiges from the civilizations that developed in the Nile Valley from the late prehistoric era (c. 4000 BC) to the Christian period (4th century AD). The Creation of the Department

Portrait of J.-F. Champollion, by Léon Cogniet, 1831, Musée du Louvre, Department of Paintings © Musée du Louvre / A. Dequier The creation of the Louvre's Department of Egyptian Antiquities was not a direct consequence of Napoleon Bonaparte's expedition to Egypt between 1798 and 1801. The English confiscated as spoils of war the Antiquities collected by scholars during that trip, which included the famous Rosetta Stone, now in London. A small number of works brought back by private individuals entered the Louvre at a much later date. Jean-François Champollion was born in 1790 and grew up in this atmosphere. A talented linguist who mastered ancient and Semitic languages, he solved the enigma of Pharaonic writing in 1822. Eager to promote the Egyptian civilization and to combat the prejudices of contemporary scholars, he helped to create the Egyptian museum in Turin. He succeeded in convincing the French king, Charles X, to purchase three of the major collections that came up for sale at the time (Durand, Salt, and Drovetti). By royal decree of May 15, 1826, he was appointed curator of a new department in the Louvre that was inaugurated on December 15, 1827. Enriching the Collection

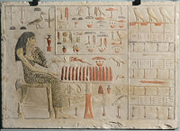

Stele: princess Nefertiabet and her food Old Kingdom, 4th Dynasty, reign of Cheops (2590-2565 BC) © Musée du Louvre/C. Décamps Prior to Champollion, the Muséum Central des Arts exhibited Egyptian statues from the former royal collections. Several major sculptures were added to this collection under Louis XVIII, including Nakhthorheb and Sekhmet. The Louvre sent French archaeologist Mariette to Egypt, where he discovered the Serapeum at Saqqara. Between 1852 and 1853, he sent 5,964 works to Paris, including the famous Seated Scribe. He became the first director of Egyptian Antiquities and protected the sites from pillagers. There followed an era during which Western museums shared objects unearthed at archaeological sites directed by scientists on concessions attributed by the Egyptian government, notably for the excavations of Abu Roash, Assiut, Antinoöpolis, Bawit, Medamud, Tod, and Deir el-Medina. Certain major works entered the museum through the generosity of individuals: American collector Atherton Curtis bequeathed 1,500 objects before and after World War II, and the Société des Amis du Louvre has provided constant support, as in 1997, with the rare statue of Queen Weret. The Current Layout

Egyptian Antiquities, Room 12: The Temple, Musée du Louvre, Paris © 2008 Musée du Louvre / Angèle Dequier "I'm thrilled just thinking about what I have to show you...this interesting series of monuments that reveals the cult, the beliefs, and the public and private life of an entire people before your eyes," wrote Champollion in 1827, summing up his encyclopedic vision of the museum. Art was only one of the aspects of the collection; inscriptions on stone and papyrus, everyday artifacts, and religious objects were all viewed from a historical and ethnological perspective. Certain decisions had to be made in 1997 during the Grand Louvre renovation project. The collection was distributed on two different floors. It was impossible to arrange the works by period, as the heaviest objects had to remain on the ground floor. This floor features a thematic installation centered on the major aspects of Egyptian civilization. It occupies rooms 1 through 19, together with the temple room (12) and the sarcophagi room (14). The first floor (rooms 20 to 30) presents a chronological approach, highlighting the different historical periods and the development of Egyptian art. |

||